A syllabus for Thanksgiving break

Last night after Leta completed her nightly bedtime reading, I pulled the covers back and to the side so that I could sit next to her legs, my own dangling off the side of the mattress.

“Leta, do you have any black kids in your class?” I asked her.

“I know that’s why we needed to watch what happened tonight,” she began, “but I don’t see people that way. We’re all the same—“

“Are there any black kids in your class?” I pressed.

“Mom, skin color doesn’t matter to me. I treat everyone the same.”

Her generosity of spirit is palpable, and everyone who knows Leta can feel it. It’s an energy she radiates. She has a special way of handling and befriending kids who are far different from her, kids who are far younger, even, a personality trait enhanced by weathering the daily blows of a demanding and dimpled younger sister who physically tugs at her every limb. My child is forgiving to a fault and comes homes often to ask how she can better mend the broken fences between dueling sets of friends where many times she has been the target of the adolescent vitriol.

Leta is a peacemaker.

Last night I sat there struggling with the duty I have to destroy that innocent notion of hers, a notion born of my ignorance and my privilege, the privilege shared by so many other well-intentioned but naive white parents who somehow think that not talking about race is in any way whatsoever going to help fix racism. We are, in fact, actively strengthening a system that continues to devalue and discard the lives of black people.

White people have to “see” it and fix it: me and you and even you, a white person who grew up in the slums of Nashville, managed to scrap and save and make a life for yourself and, nope, we never hear you complain. EVEN YOU. Leta and those determined enough in her generation will have to help us finish the work.

My generous child needs to see “black.” She needs to understand that those classmates of hers will go through life with a radically different set of experiences and fears that stem from the color of their skin. Yes, it’s a lovely notion that we are all the same, except we live in a country whose very foundation was instituted on the subjugation and continuing dehumanization of black people. She will never have to worry that the color of her skin will arouse suspicion. She will never have to worry that the color of her skin might get her harassed or, god fucking forbid, shot and killed and left to bleed and die in the middle of the street.

Last night I destroyed that innocence and began a lifelong conversation and study of race with my child.

Before you fire off an email to me or leave a comment about how you are so damn tired of everything being about race, so tired of black people blaming white people, so tired of being told that your hard work is not the very thing that is responsible for your success—you studied, you hustled and worked late shifts, you came from a family with no means and yet you have made a nice life for yourself and your family. No one in this discussion is trying to take that away from you.

First, from my friend Kristen:

White privilege isn’t about me individually. It’s not a personal attack. White privilege is a systemic cultural reality that I can either choose to ignore, or choose to acknowledge and attempt to change. It has nothing to do with my worth as a person or my own personal struggle.

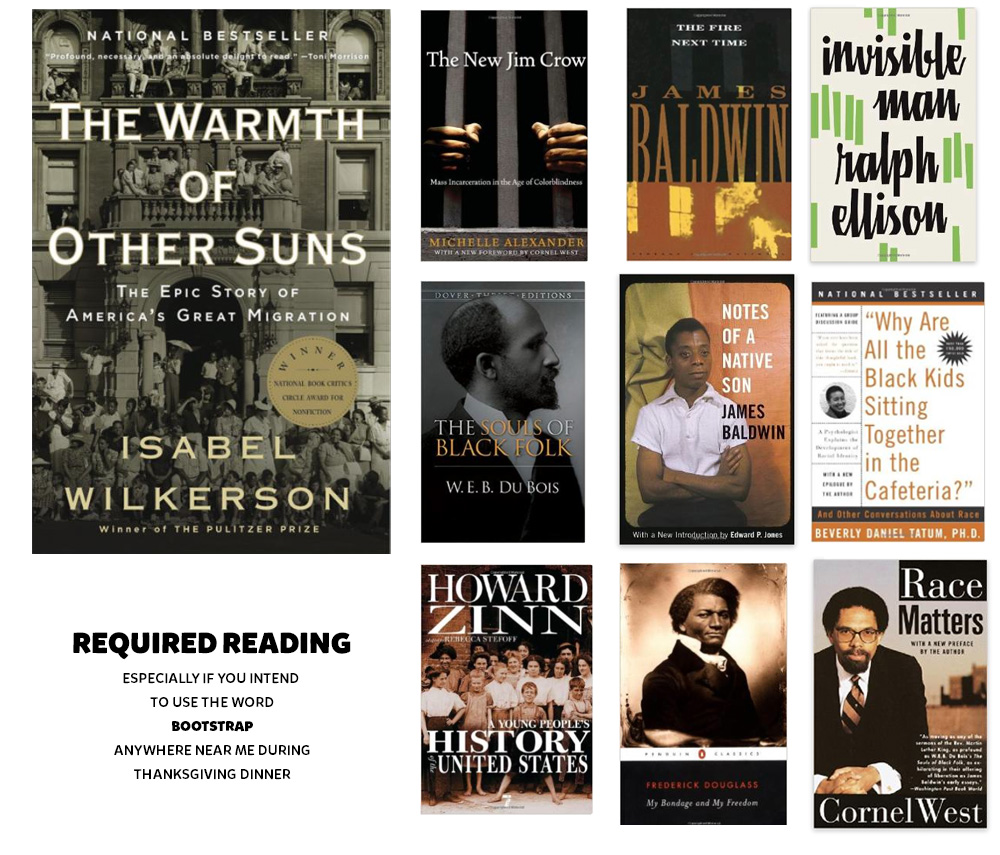

Second, go now and read the book The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. Absolutely nothing in the last twenty years of my life has changed me more than the journeys in these pages, journeys that have gone unheard for far too long by white people like myself:

Over the course of six decades some six million black southerners left the land of their forefathers and fanned out across the country for an uncertain existence in nearly every other corner of America. The Great Migration would become a turning point in history. It would transform urban America and recast the social and political order of every city it touched. It would force the South to search its soul and finally to lay aside a feudal caste system.

Those six decades did not occur in the 19th century. This was a 20th century phenomenon. My mother and father were born and raised in the South during this time when black people were routinely maimed, hosed or killed while seeking basic human rights. The South not only turned its eye to these atrocities, it encouraged and rewarded them. What this book so masterfully illustrates is the system that was orchestrated and has persisted into 2014, a system of inequality that in no way refutes that you are a hard-working white person, but it will force you to take an uncomfortable look at how far ahead your starting line was set in comparison to your black counterpart:

Multiplied over generations, it would mean a wealth deficit between the races that would require a miracle windfall or near asceticism on the part of colored families if they were to have any chance of catching up or amassing anything of value. Otherwise the chasm would continue, as it did for blacks as a group even into the succeeding century. The layers of accumulated assets built up by the better-paid dominant caste, generation after generation, would factor into a wealth disparity of white Americans having an average net worth ten times that of black Americans by the turn of the twenty-first century dampening the economic prospects of the children and the grandchildren of both Jim Crow and the Great Migration before they were even born.

Three, go read the rest of these books and open your heart. Be generous. Stop getting defensive. Stop blaming. Stop believing that eye witnesses will lie while simultaneously clutching to the notion that law enforcement never will. Stop insisting that the judicial system is infallible. Stop criticizing the response of an oppressed group of people to their oppression.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria: And Other Conversations About Race

A Young People’s History of the United States: Columbus to the War on Terror

My Bondage and My Freedom (Penguin Classics)

Four, remove the word “bootstrap” permanently from your vocabulary.

Many thanks for Kristen and Kelly for giving me the gift of the benefit of the doubt. You woke me up.