I done wrote me some words on dead trees!

Yeah. So. I’m not not gonna lie. Today is a pretty big fucking deal for me. Huge AF. And it’s all happening in the middle of a gigantic, unending move and a kid starting high school and somehow we shoved a summer’s worth of missed piano lessons into a two-inch corner of time. My dad has been in and out of the hospital for over a month, and even though I know where all the passports are we lost one of Marlo’s stuffed puppies and I have at various points over the last four weeks wanted to give up and fall over. But I haven’t. And today sort of reaffirms why I haven’t.

I haven’t because I’m better. I haven’t because I’m happy. And I’m happy because of science.

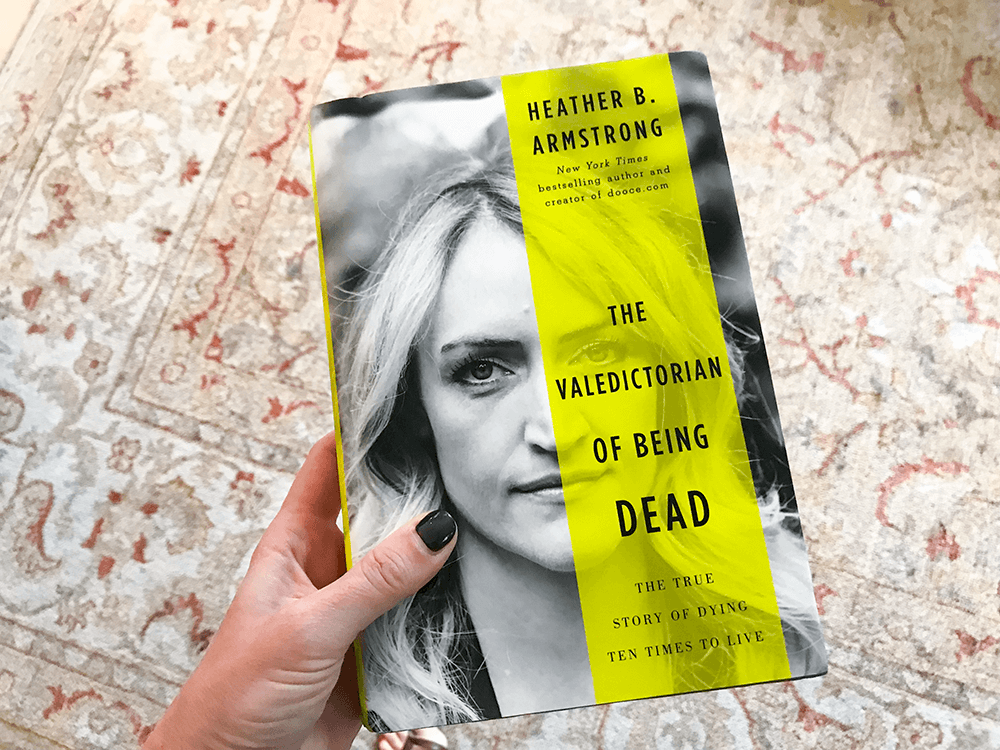

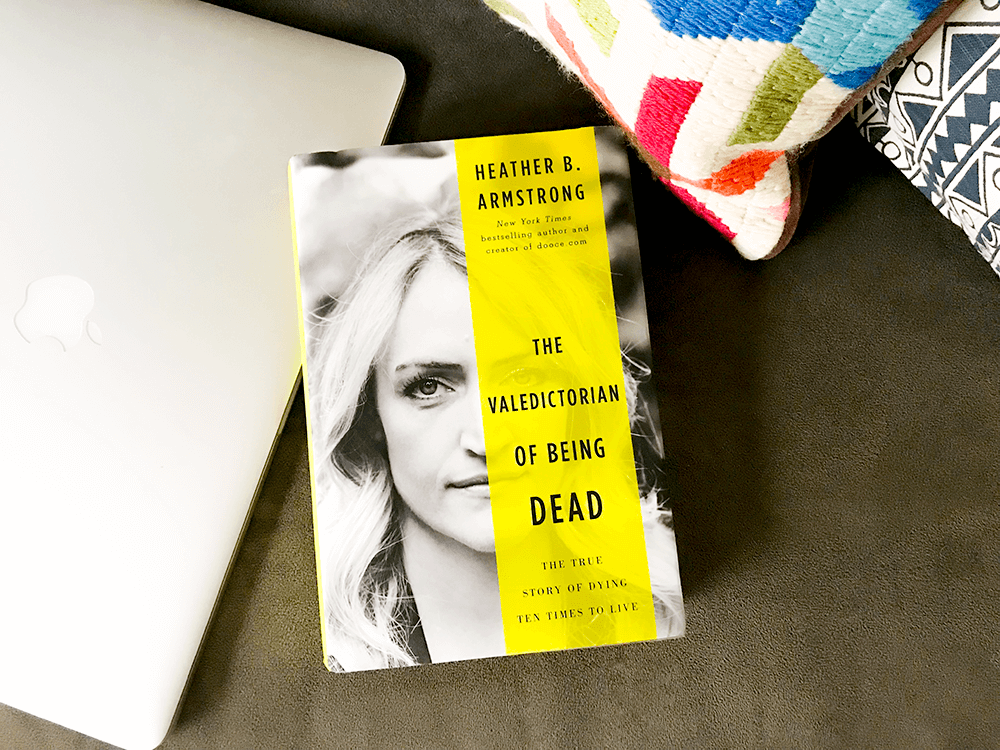

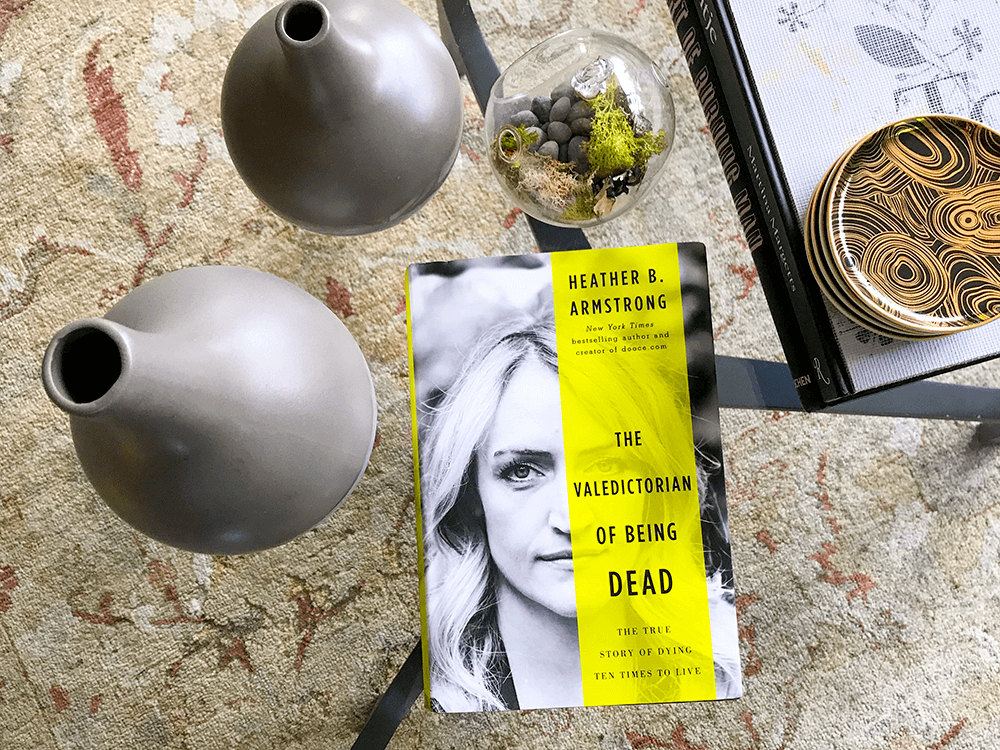

Today my book The Valedictorian of Being Dead: The True Story of Dying Ten Times to Live is available for pre-order. And the cover is finally live. Many thanks to Chad Kirkland once again for his amazing work. And to Dr. Brian Mickey for saving my life.

You can pre-order it at all these places:

The book doesn’t drop until April 23, 2019. I know that seems a bit far off but the final edits are due this week—I can’t tell you how fun it is to try to finish a book while shoving piano lessons into my jowls and moving 1300 square feet of furniture in my car. So fun. Like a goddamn flying unicorn that shits glitter and retweets the President. On purpose.

But we want to get this right. I want to get it right for those who would benefit most from reading it. Yes, I wrote it for those of us who have suffered bouts of debilitating depression, bouts that have interfered with our ability to live life. But I also wrote it for those who live with us, those who are related to us, those who are our friends and don’t understand how or why we can’t just snap out of it. I wrote it for the children who have been living with the idea that it is or was all their fault so that they might be able to let that go. It is and was not their fault.

It’s not your fault.

I have experienced tremendous satisfaction in my career as a… blogger? I have written three books before this one, and I told Leta to tell people that I’m a writer when people ask her what her mother does for a living. Because when you say, “Blogger!” people tend to ask a lot of probing questions that require complicated answers. I told Marlo to tell her friends that I’m a stripper and can pole dance like no one’s business. Anyone in Utah would follow that up with nothing other than thoughts and prayers.

But I can say without any doubt or hesitation that I have worked harder on this project, this book, than I have on anything else in my profession. And this is the most important work I have ever done. Nothing in this book appears on this website or anywhere else. I started it on a rainy morning in Paris last year—a morning following a ceaseless downpour that broke records. It rained more in one hour than it had ever rained in an hour in Paris since they had been keeping records. They had to close over a dozen metro stations because of flooding.

As inconvenient as that was for so many, I found it somewhat poetic given the subject matter of those first few pages.

And then I put the rest of my professional life on hold at the end of last year and the first half of this year to write the whole thing. There’s an author I follow on twitter who tweeted during those months that her answer to people who ask, “How’s writing the book going?” is, “First of all, fuck you.” And that’s it.

She couldn’t have summed it up better. You should follow her.

It’s been an epic fucking journey, all of it—the 18 months of crippling depression, the experimental treatment, the complete turnaround, the switch that got flipped, falling in love and writing it all down. I’m really proud of this work. And I am so happy that I lived to bring it to life.

Also, as I did with It Sucked and Then I Cried I plan to offer to sign your book with a personal inscription and a few little extra tokens of appreciation if you send it to me with a prepaid envelope.

Thank you, those of you who have stuck with me through all of this. You helped save my life, too.

And, finally, thank you Mom and Rob.