“My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still”

Tomorrow marks the tenth anniversary of the day that I checked myself into University Neuropsychiatric Institute because of a debilitating case of postpartum depression, one that had pushed me to a terrifying edge. I had seen that edge from a distance and lingered near it from time to time since high school, but on August 26th, 2004 my toes hung off of the side and I stared down at the nauseating height beneath me: I wanted to commit suicide. I knew that if I did not check myself into the hospital that day I would carry it out.

I had a plan, knew every detail of it, the timing and the tools, the words on a note I’d leave behind.

That last sentence seems so methodical and cold and detached, and it some ways I guess it is. Depression is so vicious that it mutes the ability to handle pain in any rational way. In fact, it’s such a dangerous condition that even in the absence of pain, even in the absence of any real reason to be sad or hurt or frustrated, it can cause one’s brain to shut down any capacity to cope. Cope with what? Breathing. Having to leave the bed. Sunlight.

How could I plan my own death in such a disconnected way? I’d be abandoning my family, my beautiful newborn child. She’d grow up without her mother and forever grapple with the devastating fact that her mother chose death over a life with her. I’d never see her walk or talk or score a superior score at her piano performance. I’d never get to curl her hair the day she started fifth grade.

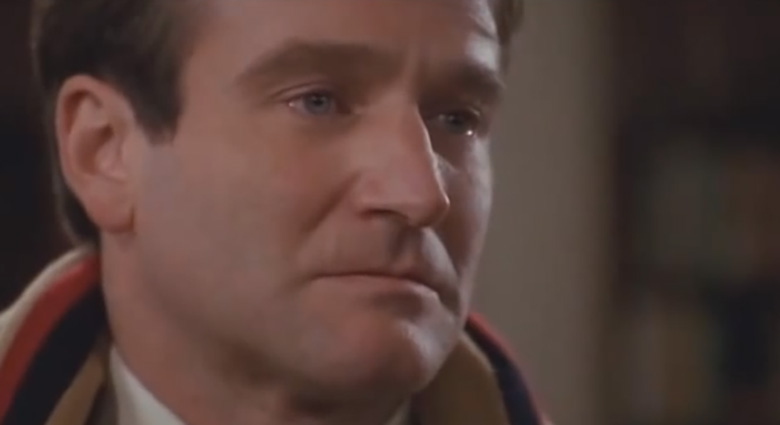

Robin Williams’ recent suicide brought this subject into our collective conversations, and while I knew some people would shake their heads and ask how someone could be so selfish, actually hearing that opinion infuriated me just as much as if I hadn’t seen it coming like a freight train. How dare he leave his family? He had everything a human being could ever want: money, a home, a family who loved him, success, friends, admiration from fans around the world. He robbed all of us of the potential work he would put into this world.

While reading some of the more forgiving and beautiful tributes to Williams and his genius, I came across a quote from David Foster Wallace that, more than anything I have ever read about this condition, sums up what I was feeling on that Thursday morning in 2004:

The so-called “psychotically depressed” person who tries to kill herself doesn’t do so out of quote “hopelessness” or any abstract conviction that life’s assets and debits do not square. And surely not because death seems suddenly appealing. The person in whom Its invisible agony reaches a certain unendurable level will kill herself the same way a trapped person will eventually jump from the window of a burning high-rise. Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; i.e. the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors. It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling “Don’t!” and “Hang on!”, can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling.

That quote is a goddamn gift. I wish every person who has ever had suicide affect them personally could read it and understand that it’s not about choosing death. You may feel abandoned and hurt and outraged, and you have every right to feel those things. But try to understand that in a mind that compromised by depression it sees life as a more terrifying option than death.

Last December my friend Stacia’s fiancé committed suicide. As friends and family gathered immediately to her home I waited until the right moment to pull her aside and listen to her pain which at the time was so bone-crushing that I thought her tiny frame would collapse beneath the weight of it. I held her as she sobbed and screamed and pounded her fists into her thighs, a wailing, “WHY!” punctuating every sentence. I did not know about that quote at the time, but I did finally pull her close and say, “I know you are angry and hurt. And you’re going to be angry and hurt for a long time. But I know where he had to be to do this to himself. I know that kind of pain. I have lived with that kind of pain, and I know that you loved him so much that if you had the tiniest glimpse of the agony he must have been feeling in that moment that you would grant that he did not do this to himself. His depression and suffering did this to him.”

Stacia and I have always been close since we met in 2009, but since her fiancé’s suicide our friendship has become one of the strongest I have ever had. I have spent many nights with her listening to her cry, holding her as she continued to ask why, as she talked of the plans they had made, the memories they had already created. Early on in her grief while listening to the anguish in every word that she spoke I had a sudden realization that if her fiancé could somehow witness this devastation, this ongoing trauma that will last for years, this haunting unknowing that will come back in waves throughout the rest of her life that maybe it would have been the one thing that could have pulled him back from that edge. The grief you might cause when you think about suicide is very abstract. It’s not a real thing, at least not in the confines of your compromised brain. Often you have convinced yourself that no one will miss you.

If he could touch her grief with his hands would it have mitigated his own?

My friendship with Stacia in the last year has shown me the very real, very tangible wreckage that his suicide has caused. I have been able to hold in my hands the heartache that would have plagued my family had I not checked myself into the hospital. I have wrapped my arms around a sobbing body, again and again and again. Robin Williams himself played a character who said “suicide is a permanent solution to temporary problems,” and I could not agree more, obviously. As much as I want to share the quote from David Foster Wallace with those affected by suicide, I in equal measure want to share the aftermath that suicide causes to those in the throes of that kind of depression.

In May while I was with Stacia in Maui she shared with me a journal of writing that she had been keeping since her fiancé’s death. It compelled me to tears, a wobbly mess of tears and sorrowful recognition. When I heard about Robin Williams and the ensuing chatter about suicide, I asked her if I could share some of what she has written. Seeing as it is the tenth anniversary of you, my readers, urging me to get help and thus being an integral part in saving my life, I wanted to share this particular side of the story. Tomorrow I will publish several excerpts from that journal. I hope you will read it and share it with those you know who might need it.